📞 Secret World No.1: SOS

It was New Years Day when Doug Nidever blacked out. One moment, the 65-year old climber was about 100 feet up Yosemite’s frozen Chouinard Falls. The next, Nidever was plummeting down a wall of ice. He thinks he fell about 50 feet, with his fellow climbers lowering him the rest of the way. Sure, he had enjoyed a few drinks as the calendar flipped to 2018, but the party had stopped — and sobered up — long before reaching the falls.

Nidever has worked as a professional mountain guide for the past 35 years. He spent the 70s and 80s with Yosemite’s Mono County Rescue, responding to ice climbers, rock climbers, hikers, and skiiers in distress, and teaching others how to do the same. Now he was the one that needed saving, and as fate would have it, Mono County Rescue was on the way. “I told those guys, after all those decades of putting people in a chopper, it was kind of a treat to get a ride out,” Nidever told me with a laugh from his home in June Lake, California earlier this summer. When his rescuers arrived, Nidever was strapped to a litter and lifted away by helicopter. Low blood pressure was to blame for the blackout, he later learned. In spite of Nidever’s insistence he could walk 45 minutes to the nearest road, a fellow climber with a satellite phone had the foresight to call for help.

A few years ago, I was idly looking at GPS running watches — the kind that can track your pace and distance — and landed on Garmin’s website. The company makes a wide range of products, used by everyone from truckers to helicopter pilots, but its GPS emergency beacons caught my eye. My partner and I go camping a few times each year, and one of those trips is usually backcountry — sometimes canoeing, sometimes hiking, sometimes both. If you get into trouble where cell signals can’t reach you, you can hit the SOS button on one of these beacons to call for help and let search and rescue crews know where you are. I figured this was the sort of thing that would be coordinated by a regional 911 dispatch centre, but Garmin’s website said the emergency monitoring service was actually offered by a company called GEOS Worldwide. I made a mental note to follow up.

It turns out that, anytime someone calls 911 on a satellite phone, or presses the SOS button on a dedicated GPS tracker — anywhere in the world — those messages typically go to one place: The International Emergency Response Coordination Center, or IERCC, about an hour outside of Houston, Texas. The center has coordinated more than 10,000 rescues in 169 countries, and responds to anywhere from 30 to 60 requests each day. Whether you’re a hermit in the Scottish highlands in medical distress, or a kayaker in eastern Tajikistan with altitude sickness (true stories) the IERCC is your point of first contact. Every hour, every day of the year, a rotating team of six watchstanders determine the closest available search and rescue team and coordinate the response. In Nidever’s case, after his ice climbing fall, the IERCC pointed Mono County Rescue his way.

I filed the idea away, and was finally able to return to it this year. I wrote about this very strange, unique, important service for Bloomberg Businessweek. The story came out this month, in print and online. I’m very proud of it, and I think it’s a good indication of where my head is at these days. It’s the ideal start to Secret World.

Of course, there’s always stuff that never quite makes it into a piece — details that either get cut for space, or don’t really fit the tone or pace. In the story we published, there’s this brief line:

The IERCC’s headquarters are in a somewhat drab, four-story office built by a Cold War-era doomsday prepper, with unusually thick concrete, backup diesel generators, a helipad, five-layer bulletproof glass, and a 40,000-square-foot fallout shelter next door. (The shelter is now a data center.)

It’s a good line — tightly written and just tantalizing enough to keep you reading (thank you, editors!). But I don’t think it quite conveys how interesting this building actually is, the details I would tell people when explaining what I had been working on:

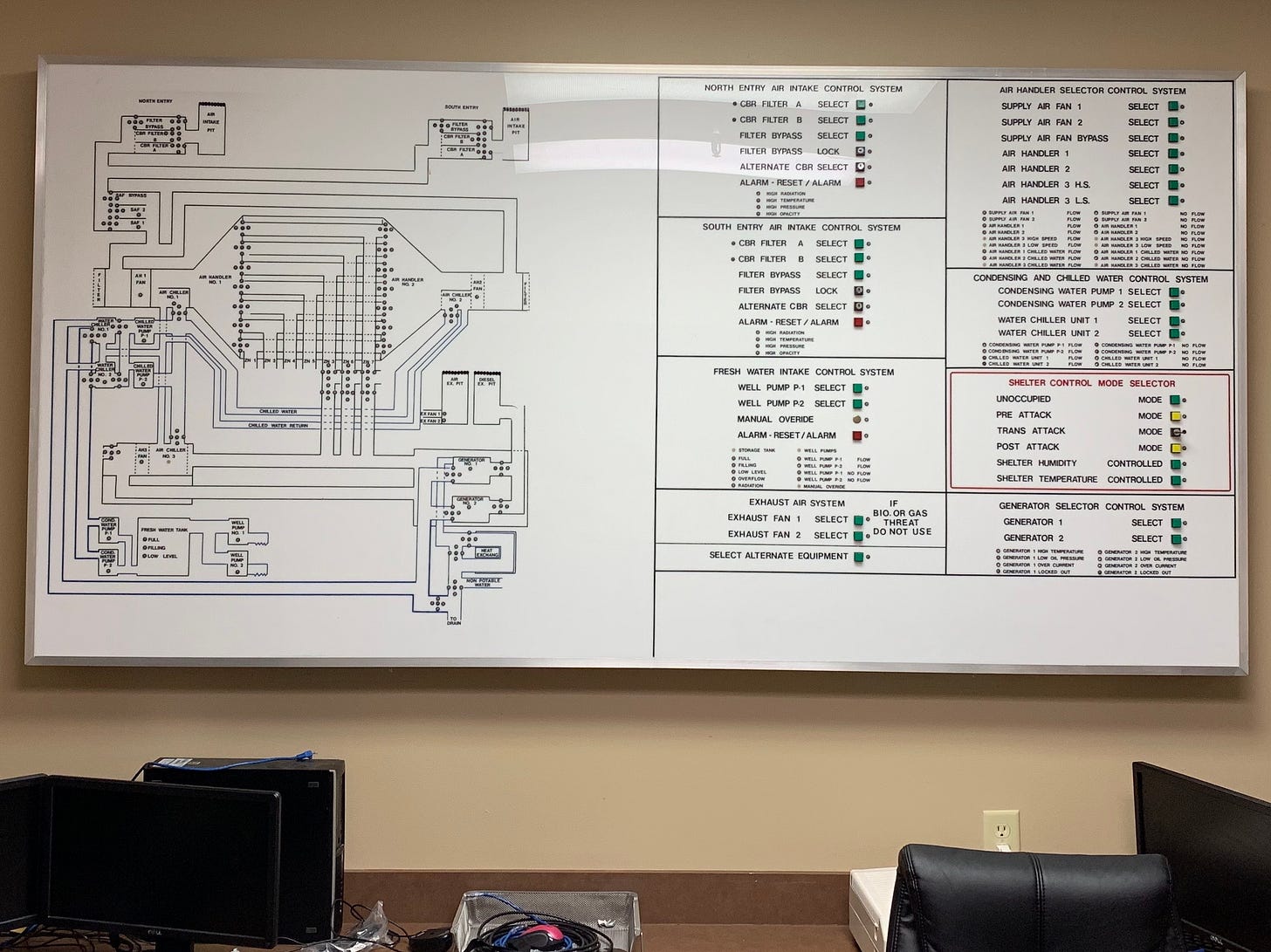

If you weren’t looking for the IERCC, you would never know it was there. It’s nestled off a state highway between a KOA Campground and plots of nearby homes. Signs warn approaching guests that they are now under surveillance, that the area is restricted, and their vehicles could be searched. You surrender your driver’s license at the gates. On the other side sits a four-story office, built in 1982 by Louis Kung, the founder of Westland Oil Development Corp. It boasts five-layer bulletproof glass, super-thick concrete, backup diesel generators, and a helipad out front. Kung lived with his wife, The Ten Commandments actress Debra Paget, on the top floor. But what few realized was that Kung, fearful of a nuclear or chemical attack, had also built an underground, self-contained 40,000 square foot fallout shelter next door. According to the current owners, it could accommodate 350 adults for up to three months, and featured decontamination showers, jail cells — with soundproof conjugal rooms — and a fully-kitted suite for surgical operations. The entrances were hidden within a pair of massive pagodas, with gunports for the armed guards to shoot at whoever who came near.

This is most likely the last major story I’ll publish for the year, but I have a handful of others in various states of research and reporting that you’ll hopefully see in the months ahead. They’re good.

Speaking of satellites: The last story I wrote for CBC News was about some work that researchers have been doing to teach drones to fly themselves when you couldn’t trust GPS. It was originally supposed to be a much larger piece, one that delved deeper into attempts to spoof, jam, and even hijack other vehicles by attacking our fragile GPS network. A key passage that didn’t make the cut:

The students sat in a small desert hut on New Mexico’s White Sands Missile Range, armed with antennas and gear. A half a mile away, a drone the size of a dinner table buzzed in place, high above the ground. They aimed their tractor beam in its direction, and prepared to attack. “The drone was just minding its business, hovering in the air, and all of a sudden — boom — they had it, and they forced it to come down toward the desert floor,” recalls Todd Humphreys, an associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin. “If the safety pilot hadn’t activated the manual control, it would have crashed.” This was in 2012, and the incident was one of the first public demonstrations that a determined attacker could overpower the GPS signals that most commercial drones use to figure out where they are in the world — allowing the attacker to effectively take control. Today, drones are far more widely used, but GPS no less a weak link.

Naturally, I was extremely interested in this story from MIT Technology Review, about a related GPS spoofing mystery in the maritime port of Shanghai.

…data showed ships jumping every few minutes to different locations on rings on the eastern bank of the Huangpu [River]. On a visualization of the data spanning days and weeks, the ships appeared to congregate in large circles.

[...]

Todd Humphreys, director of the Radionavigation Laboratory at the University of Texas at Austin and a leading authority on GPS hacking. Humphreys examined the data, but the closer he looked, the more confused he became. “To be able to spoof multiple ships simultaneously into a circle is extraordinary technology. It looks like magic,” he said.

In September, Humphreys showed a visualization of the data at the world’s largest conference of satellite navigation technology, ION GNSS+ in Florida. “People were slack-jawed when I showed them this pattern of spoofing,” he said. “They started to call it crop circles.”

The best part about all this? It might have something to do with sand.

Meanwhile…

When I decided to go back to freelancing, I made a pretty conscious decision that I would write less about tech, and more about some of the other subjects and industries that I find endlessly fascinating. One of those is, broadly speaking, the worlds of plant cultivation and agriculture, which is why I’m deeply impressed and also jealous of this story about the market for rare tropical houseplants.

Pitchfork has been reviewing Steely Dan’s most influential albums, and Alex Pappademas’ review of Gaucho is full of gems: “It’s their most obviously L.A. record, so of course they made it in New York, after spending years out West making music so steeped in New York iconography it practically sweated hot-dog-cart water.”

I’m totally enamoured with the folks dedicated to finding and testing high-quality headphones sold for cheap by no-name Chinese manufacturers.

A few years back I tried to write a story about the early days of computer animation, and while I don’t think I quite stuck the landing, I spent many weird hours learning about the Silicon Graphics computers that did all the rendering. This Twitter thread has the same energy.

Finally, this wouldn’t be one of my newsletters if I didn’t also include some music. Here’s a new song from one of my favourite artists, Destroyer’s “Crimson Tide.”

Secret World is a newsletter from writer Matthew Braga. If you’re not familiar with me or my work, be sure to check out my website, and consider following me on Twitter.

Chouinard Falls near Lee Vining canyon, Yosemite National Park. (Jonathan Fox, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The helicopter pad at the Westland Bunker, where the International Emergency Response Coordination Center is based (Matthew Braga)

Remnants of the bunker. (Matthew Braga)